Living with OCD: A Disorder, Not a Quirk

OCD — one of the most misunderstood mental illnesses.

Trigger warning: This article mentions suicide and OCD-centered intrusive thoughts.

Every single thing in my room was packed in boxes, ready for me to go to college.

I was ten years old.

For as long as I can remember, I have shown symptoms of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). When I was in elementary school, I feared not being prepared enough for college, so I packed nearly a decade in advance. Years before that, I was fixated on the idea of hating everyone – I would timidly ask my mom, “What if I hate you?” I was confused by what seemed like my voice talking down to me, internally criticizing every emotion and believing every thought I had was a fact. Around the same age, I also wasn’t sleeping because I was consumed by the idea of the world ending and I’d be the only one left. In middle school, I was obsessed with my sexuality. Did I think that girl was pretty, or am I secretly attracted to her?

In high school, I had to count the wrinkles on my bed before I left my room. My freshman year of college, OCD ran my life more than ever before. I was often late because I had to tap everything in my dorm in patterns of 2s, 3s, and 4s. I had to read every school assignment, email, and message an endless amount of times to ensure I absorbed all the information. Everything I did had to be counted – every motion, every thought could not go unnoticed.

I kept these behaviors and urges as undercover as I could. Eventually, a friend at a sleepover noticed enough to say something and encouraged me to get help. A sleepover was completely out of my routine, so my compulsions felt more urgent and my mind was completely occupied with fulfilling them. As I was attempting to subtly count everything in my organized pile of belongings my friend questioned me, emphasized the importance of confiding in my parents, and assured me that I was okay – I just likely had OCD.

I drove home and immediately called my parents, voice shaky but I knew talking about it and taking action was necessary in order for me to have a better, livable life.

I was 18 when I was diagnosed with OCD, but have shown symptoms since I was a child. This is not abnormal – most are not diagnosed with OCD till they are young adults despite showing symptoms years prior, or are misdiagnosed with anxiety, according to OCD-specialized therapist (with diagnosed OCD herself) Berenice Torruco. “To be diagnosed with OCD, you need to have obsessions which are intrusive thoughts, unwanted thoughts, distressing thoughts, combined with compulsions,” said Torruco.

It’s been around three years since my diagnosis. During this time, I’ve visited with three therapists and suffered through nearly every theme OCD latches onto. OCD is a form of neurodivergence and is also known as the “doubt disorder.” It clings to values, making someone question everything important to them, and can “show up very different for everyone,” according to Torruco. Whether I need to be certain that I’m not a pedophile or a murderer, that I’m in the right relationship, or sick with a rare disease, OCD questions my every thought, every move, my everything.

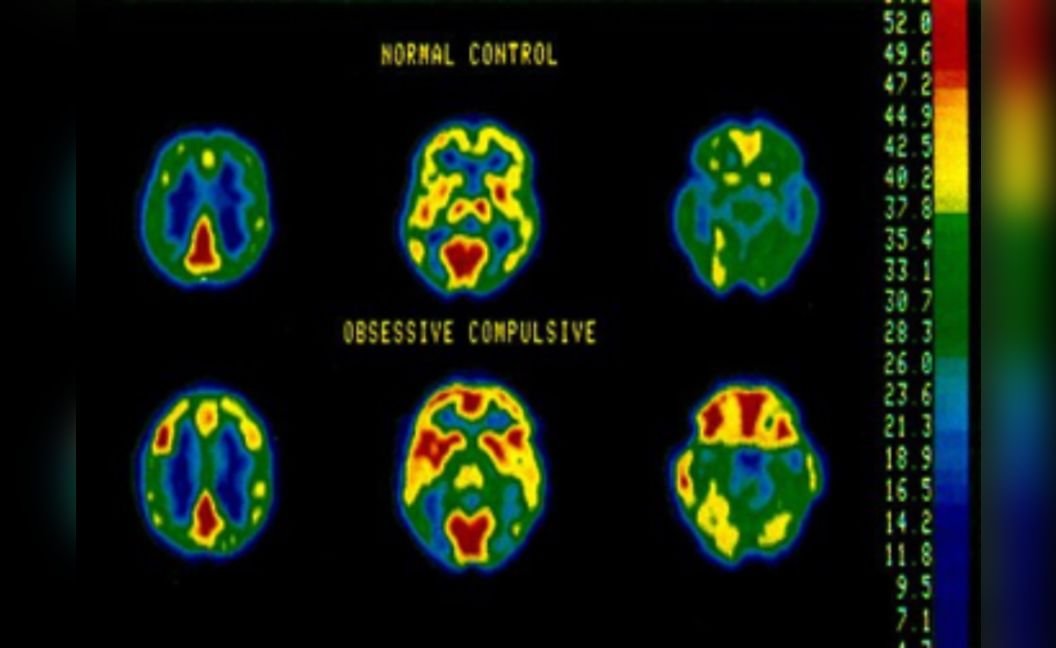

Photo courtesy of Yale School of Medicine.

And that doesn’t even scratch the surface of OCD’s impacts. OCD causes certain regions of the brain to be hyperactive and differently sized in comparison to those without OCD. This leads to increased irritability and stress that collide with any and all parts of life.

Degrading myself for having a negative thought about someone or fixating on my tone when talking, Pure OCD demands I make sure I’m a good person that makes no mistakes. “Just Right” OCD doesn’t let me finish a thought, leave a room, or focus on a conversation until I feel just right about whatever I’m compulsively doing to get there. Repeating phrases, “scanning” my room and counting items, or “organizing” conversation to ensure we touch on everything, OCD actively takes away my spontaneity and freedom.

My brain is constantly running – checking to-do lists I’ve already read, criticizing my body and compulsively picking at my skin, constantly playing violent scenarios in my head to ensure they never happen, paying far too much attention to my breathing every time I eat to make sure I’m not having an allergic reaction – OCD knows no limits.

To the outside, I look like an involved overachiever. To myself, I’m simply making certain my resumé is full and I’ve done enough. To myself, I’m crumbling under the weight of expectations that OCD has placed on me.

For years, I’ve been resentful towards those who are ignorant, making jokes that they’re “so OCD” when they like their pencils color-coded, their room is organized, or they’re a germaphobe. While people with OCD are often organized and terrified of germs, it’s more than that. OCD is an intolerant, terrifying, real disorder, not a quirk. OCD runs deep in people’s minds, controlling their lives by demanding they control as much as they possibly can.

Celebrities like Howie Mandel and John Green advocate for those with OCD and work to destigmatize the disorder, whereas Khloé Kardashian embarrassingly does the complete opposite. The media’s representation of OCD and the amount of misinformation circulating on the internet and in everyday conversations is shameful towards those truly suffering under the control of OCD – those with OCD have been found to be 10 times more likely to commit suicide than the general population.

Rather than continue to be complicit in the stigmatization of OCD and be ashamed of my diagnosis, I am inspired. I am inspired by the strength and resilience of the OCD community. I am inspired by people like Sidney Tillotson, a UT Austin finance sophomore who recently co-founded OvercomingOCD.org.

According to the International OCD Foundation, 1 in 40 adults have OCD or will develop it. When looking at UT’s campus alone, that’s close to 2,000 people suffering from OCD. Sidney created OvercomingOCD.org in hopes of finding those suffering from OCD at UT Austin and the surrounding community. “My long-term goal is to reach those 1,700 people on campus by the time I graduate,” Sidney said.

Sidney was diagnosed with OCD when she was 14. “I would say at that time it wasn't really understood what OCD was,” Sidney said. Sidney had been “suffering for a long time” and had to navigate complex, nonsensical feelings and compulsions from a young age. “I remember vividly…when I was 10 if I didn't watch 15 minutes of Teen Beach Movie, someone was going to die.”

Similar to what I struggle with, Sidney’s journey with OCD has often been centered on compulsively trying to control what people think. “It's this deep moral questioning of whether or not I'm actually a good person,” Sidney said. “Maybe I'm just lying to myself or the whole world about who I really am.”

Whether it’s unnecessarily spending hours reading through Instagram comments to make sure she didn’t say something inappropriate (when she knows she didn’t), or reading through the terms and conditions on every app and website to make sure she’s not being watched (even though she knows she isn’t), Sidney’s life often runs on fear. “I can't walk outside without all of these feelings. I can't sit in my room with all these thoughts…it won't end,” Sidney said. She’s struggled with suicide ideation, panic attacks, and has fixated on being religiously “pure” – “I started counting my ‘sins’ and would think about them every day until it just brought (me) to a point of hopelessness.”

While OCD is incessant, those diagnosed understand their thinking is irrational. “You're watching yourself from the outside and you feel like you're going crazy,” Sidney said. “Then it's like a glass mirror and everyone else is just continuing on and living a regular life, and you're watching yours fall apart.”

OCD single-handedly decides that everything is your fault. OCD keeps your brain in fight-or-flight mode, yearning for reassurance that OCD will work to get, no matter what it takes. This motivation for comfort often leads to feelings of isolation, but understanding that the OCD community is expansive helps break the stigma and gets people talking. “I understand that (having OCD) is a part of something bigger, and that makes me feel okay about it,” Sidney said.

Understanding how OCD flare-ups come and go is also paramount – breakups, stressful events, hormonal cycles and more can all impact OCD symptoms. However, destigmatizing treatment and medicine use is important for anyone experiencing mental health challenges. Someone with OCD has incredibly low serotonin levels and typically requires around 150-200 milligrams of an SSRI (antidepressants) to function similarly to those without OCD, along with exposure/response prevention (ERP) therapy and/or eye movement desensitization/reprocessing (EMDR) therapy.

As I sat with Sidney talking about our journeys with OCD, a girl came up to us and said, “I just wanted to come up and say how much I love what you're talking about because I had such bad OCD in high school…I think it's so awesome to hear people talking about it so openly.”

Sidney and I got chills. Now, us three are all planning to get coffee together. The OCD community is there, and I want to help those feel comfortable enough to openly join it.

The road to OCD recovery is steep – “We want to learn to accept that OCD is always going to be there. Intrusive thoughts are always going to be there,” Torruco said. While there is no cure, there is help available.

“The moment you turn around and you're like, ‘You will not define me,’ it's kind of the moment where you can begin to climb on your road to the top of recovery,” Sidney said.

For those with OCD, you may feel trapped by control but you are not alone. OCD often traps me and controls my life but it does not define me, and it doesn’t define you either.